1. Introduction

The pantheon of Greek gods, with their immortal yet strikingly human traits, presents a rich tapestry of stories that mirror the complexity of human relationships. The myths of the Olympians are not just about divine powers and heroic feats; they delve into intricate narratives of love, jealousy, betrayal, and rivalry that reflect the full spectrum of human emotions (Hamilton, 1942; Graves, 1955). These stories serve more than a mere cultural function; they offer a window into the social and moral fabric of ancient Greece, showing how the gods’ relationships and conflicts paralleled human interactions (Buxton, 2004). For instance, the tumultuous love affairs of Zeus, the strategic rivalries for power among siblings, and the divine interventions in mortal wars, such as the Trojan War, all highlight how deeply these myths are intertwined with human experiences (Kerényi, 1951; Morford et al., 1999).

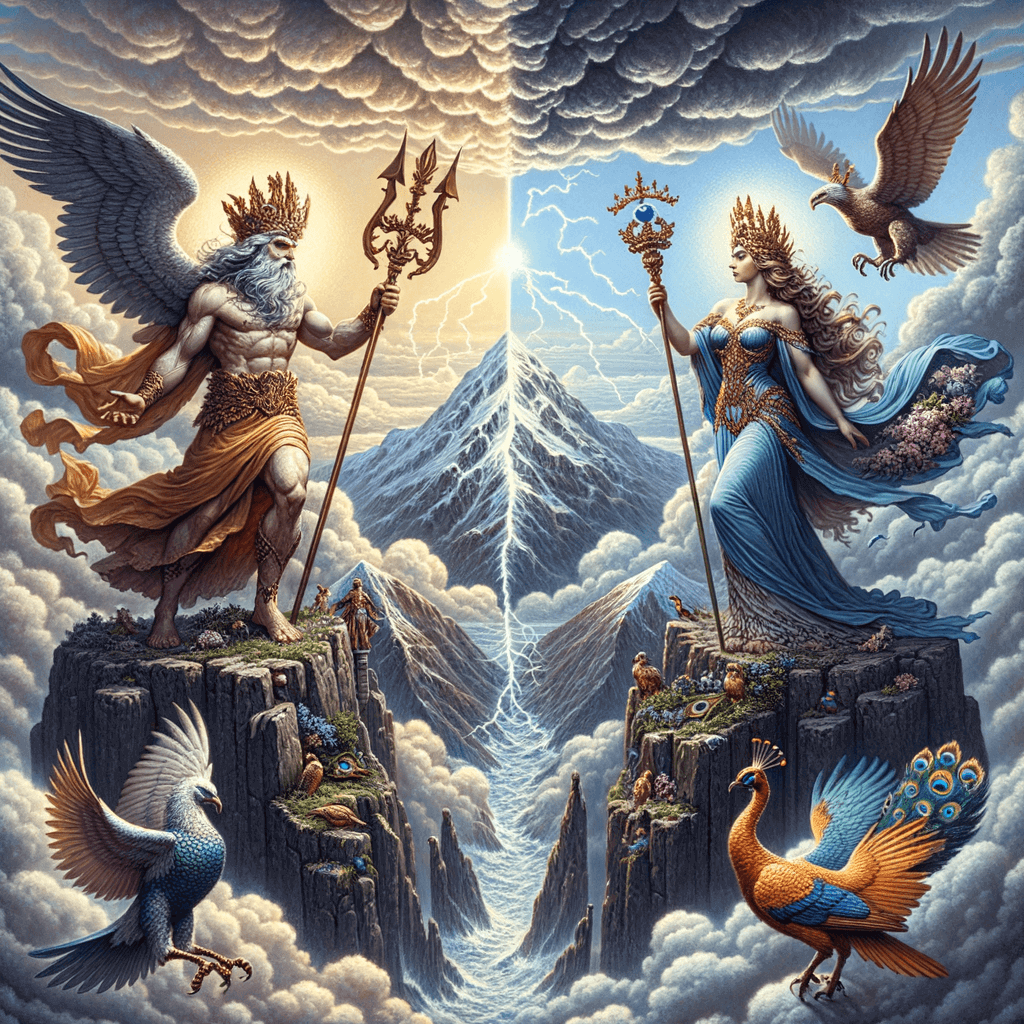

Moreover, the myths of the Olympians provide insights into ancient Greek societal norms and values, illustrating how the divine narratives influenced and were influenced by human societal constructs. The portrayal of gods like Zeus and Hera, or Athena and Poseidon, in tales of conflict and conciliation reflect not just personal but also political dynamics of the times, revealing the undercurrents of authority, loyalty, and competition that shaped ancient Greek civilization (Calame, 2003; Stafford, 2012). Through exploring these divine dramas, one gains not only a deeper understanding of Greek mythology but also a broader perspective on the ancient society that fostered these tales. These stories, rich with emotional and societal allegories, invite us to explore the timeless questions about the nature of love, power, and conflict.

2. Love, Lust, and Betrayal: The Tangled Web of Desire

2.1. Zeus, Hera, and the Many Love Affairs

Zeus, the king of the Olympian gods, is perhaps most notorious for his numerous romantic escapades, which were often marked by complex dynamics and severe repercussions. His relationships with mortals and goddesses alike, including Io, Europa, and Semele, demonstrate not only his capricious nature but also the deep interconnections between divine actions and human lives (Graves, 1955; Stafford, 2012). For instance, Zeus’s affair with Io, transformed into a cow to escape Hera’s wrath, showcases the extent of Hera’s jealousy and the lengths to which she would go to assert her position (Kerényi, 1951; Peck, 1975). Similarly, Europa’s abduction by Zeus in the form of a bull and Semele’s tragic end—burned by Zeus’s true form—illustrate the perilous consequences of divine affection (Hamilton, 1942; Morford et al., 1999).

Hera’s response to Zeus’s infidelities, characterized by jealousy and vengeful wrath, had profound implications for all involved, especially the women Zeus pursued. The goddess’s actions were not merely out of spite but also a reflection of the societal expectations and norms regarding fidelity and the status of women in ancient Greek society (Calame, 2003; Lyons, 2012). For example, Hera’s persecution of Io involved a series of transformations and escapes, which symbolize a narrative of struggle and resilience against divine and patriarchal power (Blundell, 1995; Goff, 2004). These stories not only entertain but also offer insights into the complexities of marital fidelity and the consequences of divine intervention in mortal affairs.

2.2. Aphrodite and the Power of Love

Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty, played a pivotal role in shaping the relationships and destinies of both gods and mortals. Her influence is evident in numerous myths where passion and desire override reason and duty, leading to both creation and destruction (Buxton, 2004; Stafford, 2012). The legend of Paris and Helen, which precipitated the Trojan War, underscores Aphrodite’s immense power, as she promised Helen to Paris, setting off a chain of events that would end in tragedy for many (Bull, 2000; Hughes, 1997). Similarly, the story of Eros and Psyche illustrates the trials and transformations that often accompany love, with Aphrodite playing a complex role as both antagonist and mother-in-law (Apostolou, 2007; Calame, 2003).

These tales not only demonstrate Aphrodite’s ability to influence and manipulate but also reflect broader themes of love, beauty, and the inherent chaos these can bring into the world. Aphrodite’s involvement often reveals the vulnerabilities of gods and humans alike, showing that even divine beings are not immune to the powers of love and desire (Gantz, 1993; Reed, 2009). The interactions between Aphrodite and other deities, as well as her manipulation of mortal fates, provide a rich framework for exploring themes of love as a potent but potentially destructive force that can transcend the divine and enter the realm of the epic and the everyday (Price, 2011; Cyrino, 2010).

3. Rivalries and Conflicts: The Olympians at War

3.1. The Rivalry between Athena and Poseidon over Athens

The mythological contest between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of Athens is a seminal story in Greek mythology, reflecting the cultural and religious values of the ancient Greeks (Morris, 1992; Neils, 1992). According to the legend, both deities were keen to claim the city and offered gifts to the Athenians. Poseidon struck the earth with his trident, creating a spring, while Athena offered the olive tree, a symbol of peace and prosperity. The Athenians, led by King Cecrops, chose Athena’s gift, deeming it more valuable, thereby making her their patron deity and the namesake for their city (Kerenyi, 1951; Palaima, 1991).

The symbolism of the gifts in this myth is profound. Poseidon’s spring, which turned out to be saltwater, represented naval power and the sea’s might, aligning with his domain as the god of the sea (Jordan, 1996). On the other hand, Athena’s olive tree symbolized not only economic prosperity but also peace, wisdom, and the sustenance of life, reflecting the attributes of Athena as the goddess of wisdom and strategic war. This story encapsulates the ancient Athenians’ values and priorities, emphasizing their preference for wisdom over brute strength and the long-term benefits of peace over the immediate advantages of military power (Burkert, 1985; Osborne, 1996).

3.2. The Trojan War and Divine Intervention

The Trojan War, one of the central narratives in Greek mythology, showcases the extensive involvement of gods in human affairs, with various deities taking sides and directly influencing the events of the war (Homer, Iliad; Latacz, 2004). The gods’ allegiances were split, with Hera, Athena, and Poseidon supporting the Greeks, while Aphrodite, Apollo, and Ares sided with the Trojans. This divine involvement is pivotal in the unfolding of the epic, as seen in Homer’s Iliad, where the gods engage in battles themselves and manipulate human actions according to their desires and conflicts (Clay, 1983; Redfield, 1975).

The reasons behind the gods’ choices in the Trojan War often reflected their personal grievances and relationships. For instance, Hera’s and Athena’s support for the Greeks stemmed from their anger at Paris for choosing Aphrodite over them in the judgment of the golden apple. In contrast, Aphrodite’s support for the Trojans was a direct result of Paris’s favorable judgment towards her (Kirk, 1985; Suzuki, 1992). The gods’ interventions had profound implications, influencing the course of battles and the fate of key characters, such as Achilles and Hector. This divine play within the human war not only dramatizes the conflict but also explores themes of fate, loyalty, and the capricious nature of divine favor (Griffin, 1980; Silk, 1987).

4. Sibling Rivalries and Family Dynamics

4.1. The Tumultuous Relationship between Zeus and Hera

The marriage of Zeus and Hera stands as a central theme in Greek mythology, emblematic of complex divine relationships characterized by conflicts, power struggles, and intense dynamics (Burkert, 1985; Graf, 2009). As the king and queen of the gods, their union was not just a personal relationship but a symbol of divine authority and governance. Zeus, known for his numerous affairs with other goddesses and mortal women, frequently incited Hera’s jealousy and wrath, leading to myriad mythological tales where Hera often took revenge on Zeus’s consorts and their offspring (Morford & Lenardon, 1999; Peck, 1975).

The power dynamics within their marriage reflect broader themes of conflict and reconciliation in the divine realm. Hera, while often depicted as vengeful and jealous, also exemplified the role of a wife seeking respect and fidelity, challenging Zeus’s authority on numerous occasions. This aspect of their relationship highlights the ancient Greeks’ exploration of marital fidelity and the consequences of power misuse within a sacred union. Their stories are not just about personal grievances but also about the balance of power and the continuous negotiation for respect and recognition within a partnership (Blundell, 1995; Pomeroy, 1994).

4.2. The Rivalry between Apollo and Artemis

Apollo and Artemis, twin siblings born to Zeus and Leto, exhibit a unique dynamic within the pantheon of Greek deities. As deities of immense power, each governed distinct domains: Apollo, the god of the sun, prophecy, and music; and Artemis, the goddess of the moon, hunting, and chastity (Homer, Hymn to Apollo; Kerenyi, 1951). Despite their powerful individual attributes, their mythological narratives often highlight moments of deep cooperation and mutual support, reflecting their bond as twins (Burkert, 1985; Stafford, 2012).

However, their relationship was not without its strains and conflicts. One notable myth involving their rivalry includes the tale of the hunter Orion, who was said to be killed by Artemis due to Apollo’s trickery, sparking a conflict between the siblings (Graves, 1960; Gantz, 1993). Such stories serve to explore themes of sibling rivalry and jealousy, even among the divine. These narratives also emphasize the complexities of family relationships, where love and rivalry coexist, shaping the gods’ interactions and influencing their roles in other myths (Hughes, 1991; Calame, 2009).

5. Conclusion

The mythological tales of ancient Greece are not merely stories of gods, heroes, and fantastical creatures; they are profound reflections of the values, conflicts, and complexities inherent in human society. These myths served multiple purposes: they were both educational and entertaining, providing moral and ethical guidelines through allegorical narratives. By personifying natural forces and human traits as gods and goddesses, these stories helped ancient Greeks navigate the vicissitudes of life, from natural disasters to personal moral dilemmas. The detailed accounts of deities like Zeus and Hera, or Apollo and Artemis, offer insights into the ancient Greek perspectives on authority, fidelity, sibling rivalry, and the consequences of human actions. These narratives encapsulate a wide range of human emotions and social dynamics, making them valuable tools for understanding ancient Greek culture and its influence on subsequent generations.

Moreover, the enduring relevance of these mythological tales lies in their exploration of universal themes such as love, desire, jealousy, and power dynamics, which resonate across different cultures and epochs. These themes are ubiquitous in human experience, making the stories timeless and continuously relatable. Whether it’s the complex relationship dynamics between Zeus and Hera, which mirror the trials and tribulations of marital life, or the sibling rivalry between Apollo and Artemis, which reflects competitive yet loving relationships, these myths provide a rich tapestry of human emotions and interactions. Their adaptability to various artistic and cultural forms—from ancient plays and sculptures to modern films and literature—underscores their continued relevance in helping us explore and understand not only the breadth of human nature but also the personal and societal challenges we encounter today.

6. References

Apostolou, M. (2007). Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology. Routledge.

Blundell, S. (1995). Women in Ancient Greece. Harvard University Press.

Bull, M. (2000). The Mirror of the Gods: Classical Mythology in Renaissance Art. Penguin.

Burkert, W. (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

Buxton, R. (2004). The Complete World of Greek Mythology. Thames & Hudson.

Calame, C. (2003). Myth and History in Ancient Greece: The Symbolic Creation of a Colony. Princeton University Press.

Calame, C. (2009). Archaic and Classical Greek Literature: A Performative Approach. Oxford University Press.

Clay, J. S. (1983). The Wrath of Athena: Gods and Men in the Odyssey. Princeton University Press.

Cyrino, M. S. (2010). Aphrodite. Routledge.

Gantz, T. (1993). Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Goff, B. (2004). Citizen Bacchae: Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece. University of California Press.

Graf, F. (2009). Apollo. Routledge.

Graves, R. (1955). The Greek Myths. Penguin Books.

Graves, R. (1960). The Greek Myths. Penguin Books.

Griffin, J. (1980). Homer on Life and Death. Clarendon Press.

Hamilton, E. (1942). Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes. Little, Brown and Company.

Homer. Hymn to Apollo. Translated by S. G. Miller, University of California Press, 1984.

Homer. Iliad. Translated by R. Lattimore, University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Hughes, D. D. (1997). Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Routledge.

Hughes, D. (1991). Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Routledge.

Jordan, D. R. (1996). “Athena and Poseidon’s Contest for Athens.” Numen, vol. 43, no. 1.

Kerenyi, C. (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson.

Kirk, G. S. (1985). The Iliad: A Commentary. Cambridge University Press.

Latacz, J. (2004). Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery. Oxford University Press.

Lyons, D. (2012). Dangerous Gifts: Gender and Exchange in Ancient Greece. University of Texas Press.

Morford, M., Lenardon, R., & Sham, M. (1999). Classical Mythology. Oxford University Press.

Morris, I. (1992). Death-Ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

Neils, J. (1992). The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge University Press.

Osborne, R. (1996). Greece in the Making, 1200–479 BC. Routledge.

Palaima, T. G. (1991). “The Nature of the Mycenaean Wanax: Non-Indo-European Origins and Priestly Functions.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 95, no. 3.

Peck, A. L. (1975). Hera: A Study in Early Greek Religion. Clarendon Press.

Peck, A. L. (1975). Heraclitus and the Art of Paradox. Oxford University Press.

Pomeroy, S. B. (1994). Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. Schocken.

Price, S. (2011). Religions of the Ancient Greeks. Cambridge University Press.

Reed, C. (2009). Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. Thames & Hudson.

Redfield, J. (1975). Nature and Culture in the Iliad: The Tragedy of Hector. Duke University Press.

Silk, M. S.(1987). Interaction in Poetic Imagery with Special Reference to Early Greek Poetry. Cambridge University Press.

Stafford, E. (2012). Herakles. Routledge.

Stafford, E. (2012). The Routledge Companion to the Study of Local Religion and Local Culture. Routledge.

Suzuki, M. (1992). Metamorphoses of Helen: Authority, Difference, and the Epic. Cornell University Press.

ByKus

ByKus Historia

Historia Logos

Logos Humanitas

Humanitas Mythos

Mythos Theologia

Theologia Persona

Persona Quid

Quid Gestae

Gestae Politico

Politico Mundialis

Mundialis Oeconomia

Oeconomia Athletica

Athletica Technologia

Technologia Medicina

Medicina Scientia

Scientia Astronomia

Astronomia Academia

Academia Lingua

Lingua Bibliotecha

Bibliotecha Instutia Online

Instutia Online Naturales

Naturales Humaniores

Humaniores Aesthetica

Aesthetica Cinemania

Cinemania Pictura

Pictura Sculptura

Sculptura Architectura

Architectura Musica

Musica Artificia

Artificia Atari

Atari