1. Introduction

The Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia were one of the oldest civilizations in world history, flourishing from the 4th millennium BC to the 3rd millennium BC (Postgate, 1992). The Sumerians developed a complex and prosperous society, characterized by advanced urban centers, sophisticated irrigation systems, and a thriving economy based on trade, agriculture, and specialized crafts (Oppenheim, 1977; Snell, 1997). The study of Sumerian economic life provides valuable insights into the foundations of early civilizations and the factors that contributed to their success (Trigger, 2003). Trade played a crucial role in the growth and development of Sumerian cities, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies across vast distances (Algaze, 1993). Agriculture, supported by extensive irrigation networks, formed the backbone of the Sumerian economy, enabling the production of surplus food and the growth of urban populations (Pollock, 1999). The social and economic structure of Sumerian society, with its hierarchical classes, specialized labor, and legal regulations, further shaped the dynamics of economic life in this ancient civilization (Liverani, 2014).

2. Trade and Commerce

2.1. Mesopotamian Trade Routes and Networks

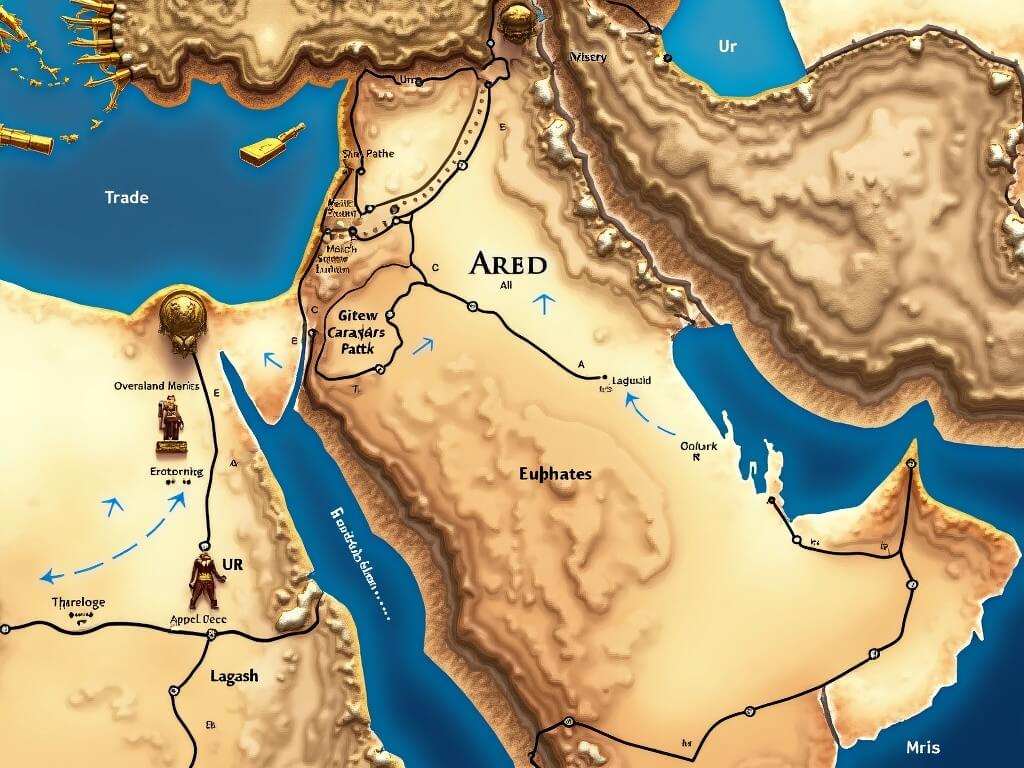

The ancient Sumerians established extensive trade routes and networks that connected their cities to distant regions, facilitating the exchange of goods, raw materials, and ideas (Lamberg-Karlovsky, 1998). One of the most important trade routes was the Persian Gulf, which allowed Sumerian merchants to access the rich resources of the Indus Valley, such as precious stones, copper, and timber (Potts, 1997). The Sumerian city of Ur, located near the coast, served as a major hub for maritime trade, with its merchants venturing as far as Oman and the Indus Valley (Kuhrt, 1995). Overland trade routes were also crucial, connecting Sumer to the Levant, Anatolia, and the Iranian Plateau (Algaze, 1993). The city of Ebla, located in modern-day Syria, was a significant trading partner of the Sumerians, with evidence of extensive commercial exchanges between the two civilizations (Archi, 1993).

The development of sophisticated transportation technologies, such as boats, donkeys, and wheeled vehicles, further facilitated long-distance trade (Sherratt, 1995). The Sumerian invention of writing also played a crucial role in the organization and management of trade, allowing for the recording of transactions, contracts, and inventories (Postgate, 1992). The use of seals and sealings, which served as a form of personal identification and authorization, was another important innovation that contributed to the growth of trade networks (Rothman, 2004).

2.2. Traded Goods and Materials

The Sumerians traded a wide range of goods and materials, both locally produced and imported from distant regions (Snell, 1997). Textiles were one of the most important Sumerian exports, with the city of Ur renowned for its high-quality woolen garments (Oppenheim, 1977). The Sumerians also traded in various metals, such as copper, silver, and gold, which were used for the production of tools, weapons, and luxury items (Potts, 1997). Timber, a scarce resource in Mesopotamia, was imported from the Levant and the Zagros Mountains, and used for construction, shipbuilding, and the manufacture of furniture (Liverani, 2014).

Agricultural products, such as grains, dates, and sesame oil, were also traded extensively, both within Sumer and with neighboring regions (Pollock, 1999). The Sumerian city of Umma, for example, was famous for its date orchards and exported large quantities of dates to other cities (Leick, 2003). Sumerian traders played a crucial role in the exchange of goods, acting as intermediaries between producers and consumers, and often organizing long-distance trade expeditions (Yoffee, 1995). The profits generated from trade contributed significantly to the wealth and prosperity of Sumerian cities, and the influence of Sumerian traders extended far beyond the boundaries of Mesopotamia (Algaze, 1993).

2.3. Economic Centers and Cities

The Sumerian economy was centered around a network of cities, each with its own specializations and economic activities (Trigger, 2003). Ur, located in the south of Sumer, was one of the most important economic centers, renowned for its textile industry, maritime trade, and the production of luxury goods (Oppenheim, 1977). The city’s strategic location near the Persian Gulf allowed it to control key trade routes and access valuable resources (Kuhrt, 1995). Uruk, another major city, was famous for its monumental architecture, such as the Eanna temple complex, and its role in the development of writing and bureaucracy (Liverani, 2014). Uruk’s economy was based on agriculture, animal husbandry, and the production of ceramics and other crafts (Pollock, 1999).

Nippur, located in central Sumer, was an important religious and economic center, home to the Ekur, the temple of the god Enlil (Zettler, 1992). The city’s economy was closely tied to the temple, which owned large tracts of land, employed numerous workers, and engaged in long-distance trade (Steinkeller, 1981). Other notable economic centers included Lagash, known for its irrigation systems and agricultural productivity (Postgate, 1992), and Umma, famous for its date orchards and the production of textiles and ceramics (Leick, 2003). The economic specialization and interdependence of Sumerian cities contributed to the development of a complex and prosperous urban society, with trade and exchange playing a crucial role in the integration of these centers (Wright, 1987).

3. Agriculture and Food Production

3.1. Irrigation Systems and Techniques

The success of Sumerian agriculture relied heavily on the development of advanced irrigation systems and techniques, which allowed farmers to harness the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (Postgate, 1992). The Sumerians constructed an extensive network of canals, levees, and reservoirs to control the flow of water and prevent flooding (Pollock, 1999). These irrigation systems were managed by a complex bureaucracy, with officials responsible for the maintenance of canals, the distribution of water, and the collection of taxes (Steinkeller, 1981). The Sumerian city of Lagash, for example, had a sophisticated water management system that included a network of canals, sluice gates, and water reservoirs (Crawford, 2004).

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers were the lifelines of Sumerian agriculture, providing the water necessary for the cultivation of crops in an otherwise arid environment (Liverani, 2014). The annual flooding of these rivers deposited rich alluvial soil on the surrounding plains, creating fertile agricultural land (Snell, 1997). The Sumerians developed techniques such as basin irrigation, which involved the creation of small, enclosed fields that were flooded with water from canals (Postgate, 1992). This method allowed for the efficient use of water and the cultivation of a wide variety of crops (Pollock, 1999).

3.2. Crops and Farming Practices

The Sumerians cultivated a diverse range of crops, including barley, wheat, and dates, which formed the basis of their diet and economy (Snell, 1997). Barley was the most important crop, used for the production of bread, beer, and animal feed (Oppenheim, 1977). Wheat was also widely cultivated, along with legumes such as lentils and peas (Pollock, 1999). Date palms, which thrived in the hot and dry climate of southern Mesopotamia, provided a valuable source of food, fiber, and wood (Potts, 1997).

Sumerian farmers employed a variety of tools and methods to cultivate their crops. The plow, drawn by oxen, was used to prepare the soil for planting (Potts, 1997). Sickles made of clay or bronze were used to harvest the grain, which was then threshed using animal-drawn sledges (Postgate, 1992). The Sumerians also developed a system of crop rotation, alternating between different crops to maintain soil fertility (Liverani, 2014). Manure from livestock was used to fertilize the fields, and fallowing was practiced to allow the land to recover between planting seasons (Pollock, 1999).

3.3. Livestock and Animal Husbandry

Livestock played a crucial role in the Sumerian economy, providing meat, dairy products, wool, and labor for agricultural activities (Sherratt, 1995). Cattle, sheep, and goats were the most important domestic animals, with large herds maintained by temples, palaces, and wealthy individuals (Postgate, 1992). Cattle were used for plowing, threshing, and transport, while sheep and goats provided wool for the textile industry and milk for the production of cheese and other dairy products (Oppenheim, 1977).

Animal husbandry practices were well-developed in ancient Sumer, with specialized workers responsible for the care and management of livestock (Snell, 1997). Shepherds and herdsmen tended to the animals, ensuring their well-being and protecting them from predators (Potts, 1997). The Sumerians also practiced selective breeding to improve the quality of their livestock, and they developed techniques for the storage and preservation of animal products (Pollock, 1999). The importance of livestock in the Sumerian economy is reflected in the detailed records kept by temple and palace administrators, which documented the number of animals, their yields, and their distribution (Zettler, 1992).

4. Social and Economic Structure

4.1. Social Classes and Hierarchy

Sumerian society was characterized by a hierarchical structure, with distinct social classes that determined an individual’s role, status, and economic opportunities (Postgate, 1992). At the top of the hierarchy were the priests and nobles, who held positions of power in the temples and palaces (Oppenheim, 1977). Priests were responsible for the administration of temple estates, the performance of religious rituals, and the management of economic activities (Pollock, 1999). Nobles, including the royal family and high-ranking officials, controlled large tracts of land and exercised political and military authority (Snell, 1997).

Below the priests and nobles were the commoners, who made up the majority of the population (Liverani, 2014). Commoners were engaged in various occupations, such as farming, fishing, and craftsmanship (Potts, 1997). They were obligated to perform labor services for the temples and palaces, and they paid taxes in the form of a share of their agricultural produce or manufactured goods (Steinkeller, 1981). At the bottom of the social hierarchy were slaves, who were owned by temples, palaces, or wealthy individuals and performed a wide range of tasks, from agricultural labor to domestic service (Postgate, 1992).

4.2. Labor and Specialization

The Sumerian economy relied on a complex division of labor and specialization in various economic activities (Yoffee, 1995). In agriculture, farmers and laborers were responsible for plowing, planting, irrigating, and harvesting crops (Pollock, 1999). Skilled workers, such as potters, weavers, and metalworkers, produced a wide range of goods for both local consumption and long-distance trade (Potts, 1997). Artisans, who were often attached to temples or palaces, created luxury items, such as jewelry, sculptures, and decorative objects (Oppenheim, 1977).

The production of textiles, one of the most important industries in ancient Sumer, involved a high degree of specialization (Snell, 1997). The process of textile manufacture, from the shearing of sheep to the weaving of cloth, required the collaboration of multiple specialists, including shepherds, spinners, dyers, and weavers (Postgate, 1992). The organization of labor in the textile industry was highly complex, with workers divided into different ranks and overseen by supervisors and administrators (Liverani, 2014). The specialization of labor in the Sumerian economy allowed for the production of high-quality goods and the efficient use of resources (Yoffee, 1995).

4.3. Law and Economic Regulations

The Sumerian legal system played a crucial role in regulating economic activities and protecting property rights (Postgate, 1992). The Code of Ur-Nammu, one of the earliest known legal codes, dating to the 21st century BCE, set out rules for the conduct of business, the ownership of property, and the resolution of disputes (Snell, 1997). The code established specific penalties for economic offenses, such as fraud, theft, and breach of contract (Liverani, 2014).

Economic regulations were enforced by a complex bureaucracy, with officials responsible for the collection of taxes, the distribution of rations, and the supervision of labor (Steinkeller, 1981). Temples and palaces, which controlled large portions of the economy, had their own administrative systems for managing economic activities (Oppenheim, 1977). Merchants and traders were subject to various regulations, including the payment of taxes and the use of standardized weights and measures (Potts, 1997). The Sumerian legal and economic system provided a framework for the smooth functioning of the economy and the protection of individual and institutional rights (Postgate, 1992).

5. Conclusion

The ancient Sumerian civilization developed a complex and prosperous economy that relied on a combination of trade, agriculture, and a hierarchical social structure. The extensive trade networks established by the Sumerians connected their cities to distant regions, facilitating the exchange of goods, raw materials, and ideas. The Sumerian merchants played a crucial role in the growth of long-distance trade, with cities like Ur and Uruk serving as major economic centers. The trade of textiles, metals, timber, and agricultural products contributed significantly to the wealth and influence of Sumerian cities. Additionally, the development of advanced irrigation systems and techniques, along with the cultivation of a diverse range of crops and the practice of animal husbandry, allowed the Sumerians to create a thriving agricultural economy in the challenging environment of Mesopotamia.

The Sumerian economic system was underpinned by a hierarchical social structure, with priests, nobles, and commoners each playing specific roles in the production, distribution, and regulation of goods and services. The specialization of labor and the division of work in various economic activities, such as agriculture, crafts, and trade, enabled the Sumerians to achieve high levels of productivity and innovation. Furthermore, the Sumerian legal system, with its emphasis on property rights, contracts, and standardized measures, provided a stable framework for economic transactions and the resolution of disputes. The lasting impact of the Sumerian economic model can be seen in the development of subsequent civilizations in the Near East and beyond, with many of the fundamental principles and practices established by the Sumerians continuing to shape economic thought and behavior to this day.

6. References

Algaze, Guillermo. “The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization.” University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Archi, Alfonso. “The City of Ebla and the Organization of Its Rural Territory.” Berytus, vol. 41, 1993, pp. 5–22.

Crawford, Harriet E.W. “Sumer and the Sumerians.” Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN: 0521533384.

Kuhrt, Amélie. “The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC.” Routledge, 1995. ISBN: 0415167636.

Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. “The Rise of the City in the Near East.” Archaeology, vol. 51, no. 2, 1998, pp. 26–36.

Leick, Gwendolyn. “The Babylonians: An Introduction.” Routledge, 2003. ISBN: 0415253115.

Liverani, Mario. “The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy.” Routledge, 2014. ISBN: 0415679188.

Oppenheim, A. Leo. “Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization.” University of Chicago Press, 1977. ISBN: 0226632800.

Pollock, Susan. “Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden that Never Was.” Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN: 0521574360.

Postgate, J. N. “Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History.” Routledge, 1992. ISBN: 0415035735.

Potts, Daniel T. “Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations.” Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN: 0801485938.

Rothman, Mitchell S. “Sealing as a Craft and Knowledge System in Ancient Mesopotamia.” Technology and Culture, vol. 45, no. 4, 2004, pp. 742–763.

Sherratt, Andrew. “Reviving the Grand Narrative: Archaeology and Long-Term Change.” Journal of European Archaeology, vol. 3, no. 1, 1995, pp. 1–32.

Snell, Daniel C. “Life in the Ancient Near East, 3100-332 B.C.E.” Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN: 0300063198.

Steinkeller, Piotr. “The Administrative and Economic Organization of the Ur III State.” Archivi Reali di Ebla, 1981, pp. 19–42.

Trigger, Bruce G. “Understanding Early Civilizations: A Comparative Study.” Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN: 0521822451.

Wright, Henry T. “The Ecological Setting for the Urban Revolution.” American Anthropologist, vol. 89, no. 1, 1987, pp. 109–122.

Yoffee, Norman. “The Economics of Ancient Western Asia.” Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, vol. 3, 1995, pp. 1387–1399.

Zettler, Richard L. “The Ur III Temple of Inanna at Nippur.” Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, vol. 82, no. 1, 1992, pp. 68–121.

ByKus

ByKus Historia

Historia Logos

Logos Humanitas

Humanitas Mythos

Mythos Theologia

Theologia Persona

Persona Quid

Quid Gestae

Gestae Politico

Politico Mundialis

Mundialis Oeconomia

Oeconomia Athletica

Athletica Technologia

Technologia Medicina

Medicina Scientia

Scientia Astronomia

Astronomia Academia

Academia Lingua

Lingua Bibliotecha

Bibliotecha Instutia Online

Instutia Online Naturales

Naturales Humaniores

Humaniores Aesthetica

Aesthetica Cinemania

Cinemania Pictura

Pictura Sculptura

Sculptura Architectura

Architectura Musica

Musica Artificia

Artificia Atari

Atari