1. Introduction

Animism, one of the most ancient belief systems, posits that non-human entities—ranging from animals and plants to inanimate objects and natural phenomena—possess a spiritual essence. This worldview, deeply rooted in the traditions of many indigenous cultures, frames nature as a living, conscious entity where every element is interconnected through spiritual bonds. As such, animism offers a unique perspective that contrasts sharply with more materialistic or mechanistic views of the world. Despite its ancient origins, animism continues to influence contemporary spiritual practices and environmental philosophies, revealing its enduring relevance in a rapidly changing world.

In this blog post, we will explore the multifaceted nature of animism, delving into its core principles and historical context to better understand its foundational tenets. We will examine the rich tapestry of indigenous practices that embody animistic beliefs, highlighting specific cultural case studies and the pivotal role of shamans and spiritual leaders. Additionally, we will discuss how animism informs environmental protection efforts and modern ecological movements, illustrating the belief system’s practical applications. Finally, we will address the impact of colonialism and modernization on animistic traditions and consider the resurgence of these beliefs in contemporary spirituality. By the end, readers will gain a comprehensive understanding of animism’s significance and its potential contributions to modern society.

2. Defining Animism

2.1. What is Animism?

Animism is defined as the belief that non-human entities, including animals, plants, and inanimate objects, possess a spiritual essence. This worldview suggests that every element of the natural world is imbued with a soul or spirit, creating a universe where everything is alive and interconnected. The origins of animism can be traced back to early human societies, where natural phenomena were often explained through the presence of spirits (Bird-David, 1999). These beliefs were integral to the daily lives and cultural practices of many indigenous communities, serving as a foundation for their understanding of the world. Animism is not a monolithic belief system but rather a diverse array of practices and interpretations that vary significantly across different cultures and regions (Ingold, 2006). Despite these variations, the core tenet remains the same: the recognition of a spiritual dimension in all aspects of nature.

The basic concepts of animism include the idea that spirits inhabit not only living beings but also natural objects like rocks, rivers, and mountains. This belief fosters a sense of reverence and respect for the environment, as every element is seen as possessing intrinsic value and agency (Harvey, 2005). Animistic practices often involve rituals and ceremonies aimed at communicating with these spirits, seeking their guidance, and maintaining harmony with the natural world (Descola, 2013). These practices highlight the reciprocal relationship between humans and nature, emphasizing the need for balance and respect in all interactions. The universality of animistic beliefs across disparate cultures underscores their fundamental role in shaping human perceptions of the natural world (Hallowell, 1960).

2.2. Core Principles of Animism

The fundamental principles of animism revolve around the interconnectedness of all life, the presence of spirits in nature, and the concept of a living, conscious world. One of the central tenets is the belief that all elements of nature are interconnected through a web of spiritual relationships. This interconnectedness implies that the well-being of one aspect of the natural world is intrinsically linked to the well-being of the whole (Viveiros de Castro, 1998). Such a perspective fosters a holistic approach to life, where every action has broader implications for the environment and the community.

Another core principle is the presence of spirits in nature. Animists believe that spirits inhabit not only animals and plants but also natural features like rivers, mountains, and even weather phenomena (Tylor, 1871). These spirits are often considered guardians or custodians of their respective domains, and maintaining a respectful relationship with them is seen as vital for ensuring harmony and balance (Bird-David, 1999). This belief in a living, conscious world challenges the dichotomy between the animate and inanimate, suggesting that everything in nature possesses a form of consciousness or awareness (Ingold, 2006). Such views encourage a deep sense of respect and responsibility towards the natural world, promoting sustainable practices and a harmonious coexistence with all forms of life (Descola, 2013).

2.3. Animism in Historical Context

Historically, animism has been perceived and practiced in various ways across different cultures. In many indigenous societies, animistic beliefs formed the foundation of their cosmologies and worldviews, influencing everything from daily practices to social structures (Harvey, 2005). For instance, among the Ojibwa of North America, the concept of “manitous” refers to spiritual beings that inhabit all aspects of the natural world, guiding and influencing human affairs (Hallowell, 1960). Similarly, in the Amazonian cultures, the idea of “perspectivism” posits that humans and animals share a common spiritual essence, leading to practices that emphasize respect and empathy towards other living beings (Viveiros de Castro, 1998).

The perception and practice of animism have also evolved over time, particularly in response to external influences such as colonialism and globalization. During the colonial period, many animistic traditions were suppressed or marginalized by dominant religious and cultural forces (Descola, 2013). However, despite these challenges, animistic practices have persisted and adapted, often blending with other belief systems to create syncretic forms of spirituality (Ingold, 2006). In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in animism, both within indigenous communities seeking to reclaim their cultural heritage and among modern spiritual movements that recognize the value of animistic principles in fostering a sustainable and harmonious relationship with the natural world (Bird-David, 1999).

3. Animism in Indigenous Cultures

3.1. Indigenous Practices and Beliefs

Animism is a foundational aspect of many indigenous cultures around the world, manifesting through a variety of practices, rituals, and ceremonies that emphasize the interconnectedness of all life. In many African societies, such as the Yoruba of Nigeria, animistic beliefs are evident in rituals that honor the spirits of ancestors and natural forces. These rituals often include offerings, drumming, and dancing, which are intended to communicate with and appease these spirits (Bascom, 1969). Similarly, in the Amazon Basin, indigenous tribes like the Yanomami engage in shamanic rituals that involve the use of hallucinogenic plants to enter trance states and interact with the spirit world (Rivière, 1999). These practices reflect a deep-seated belief in the spiritual essence of nature and the need to maintain harmony with it.

In Oceania, the Maori of New Zealand practice animism through their concept of “mana,” a spiritual force that resides in all objects and beings. Traditional Maori ceremonies, such as the “haka” dance, are performed to invoke this spiritual power and connect with their ancestors (Barlow, 1991). In North America, the Lakota Sioux conduct the “Sun Dance,” a ritual that involves fasting, dancing, and sometimes piercing the flesh to offer sacrifices to the Great Spirit and seek visions (Brown, 1953). These diverse practices underline the universality of animistic beliefs in indigenous cultures, highlighting a common thread of reverence for the spiritual dimensions of the natural world.

3.2. Case Studies: Animism in Specific Cultures

In Japan, Shintoism presents a distinctive form of animism where kami, or spirits, are believed to inhabit natural objects and phenomena. Shinto rituals often involve purification rites, offerings, and festivals that honor these kami, reflecting a deep respect for nature and its spiritual presence (Bocking, 1997). Shinto shrines, often located in scenic natural settings, serve as places where individuals can connect with the kami and seek their blessings. This integration of spirituality and natural reverence is a hallmark of Shinto practice and illustrates the enduring influence of animistic beliefs in Japanese culture.

Among Aboriginal Australians, the concept of “Dreamtime” encapsulates their animistic worldview. Dreamtime refers to the time of creation when ancestral beings formed the land, plants, animals, and humans. These beings are believed to still exist in the landscape, which is therefore considered sacred. Aboriginal rituals, such as the “corroboree,” involve storytelling, music, and dance to connect with these ancestral spirits and honor their ongoing presence in the natural world (Berndt & Berndt, 1988). Similarly, many Native American tribes, such as the Hopi, believe in “kachinas,” spirits that inhabit natural elements and influence their daily lives. Kachina ceremonies involve elaborate dances and masks to invoke these spirits and ensure the community’s well-being (Titiev, 1944). These case studies demonstrate the rich diversity of animistic practices and their central role in the cultural and spiritual lives of these communities.

3.3. The Role of Shamans and Spiritual Leaders

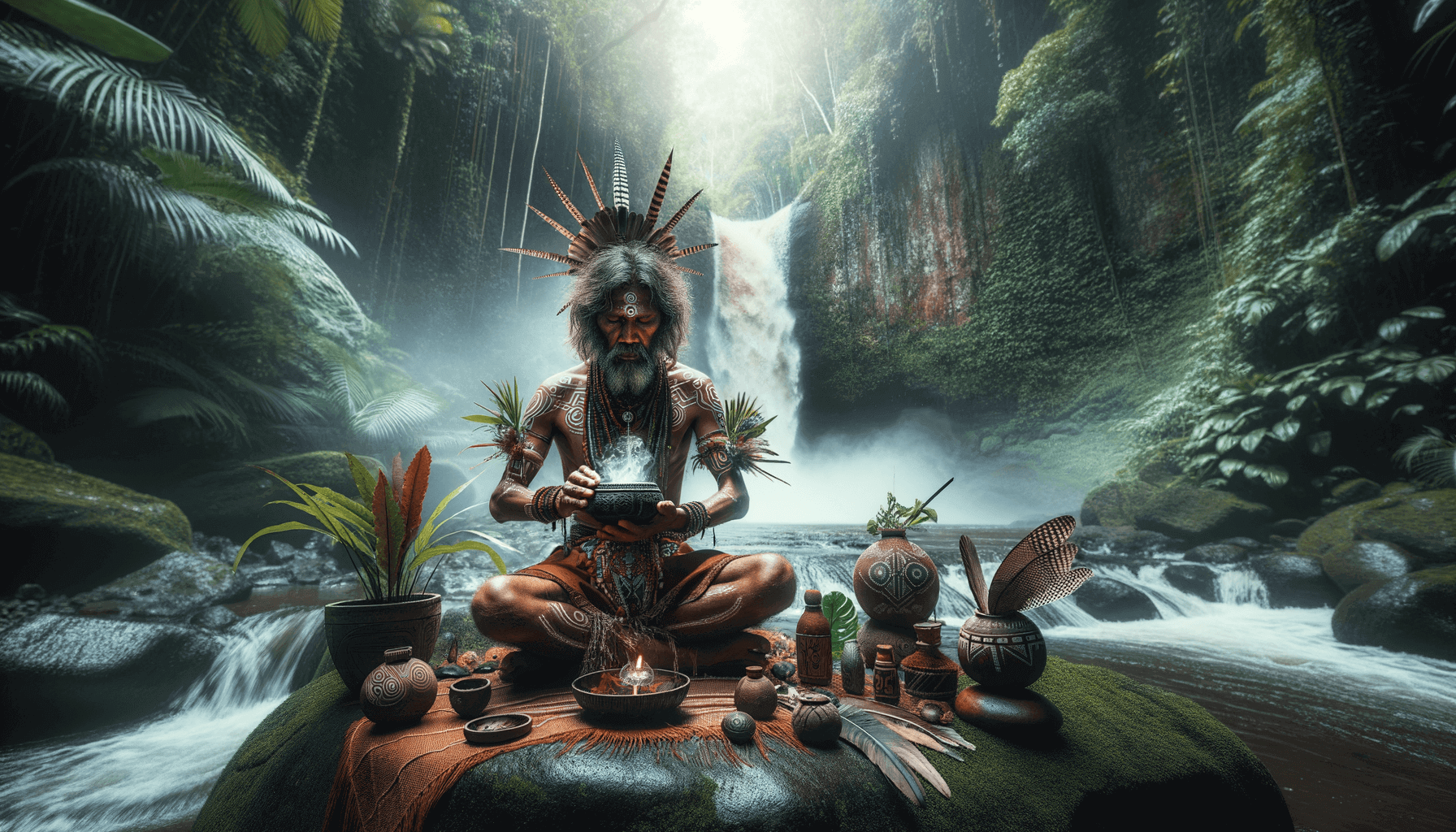

Shamans and other spiritual leaders play a crucial role in animistic societies, serving as intermediaries between the human and spirit worlds. These individuals are often believed to possess special abilities that allow them to communicate with spirits, heal the sick, and guide their communities in spiritual matters. In Siberian cultures, for example, shamans use drumming and chanting to enter trance states and journey to the spirit world, where they seek guidance and healing for their people (Eliade, 1964). The shaman’s role is not only to heal but also to maintain the balance between the human community and the natural world, ensuring that the spirits are respected and appeased.

In the Amazon, shamans of the Shipibo-Conibo people use ayahuasca, a powerful hallucinogenic brew, to facilitate communication with the spirit world. These ceremonies, which involve singing sacred songs known as “icaros,” are central to their healing practices and spiritual life (Luna, 1986). Similarly, in the Andes, Andean shamans, or “paqos,” perform rituals to honor the Apus, the mountain spirits, and Pachamama, the earth mother. These rituals often include offerings of food, coca leaves, and other items to ensure the community’s harmony with the natural world (Allen, 2002). The importance of shamans and spiritual leaders in these societies underscores the central role of animism in guiding both individual and communal life, providing a framework for understanding and interacting with the world.

4. Animism and Environmental Protection

4.1. Animism’s Perspective on Nature

Animistic beliefs inherently foster a deep respect for nature and the environment, viewing the world not merely as a collection of resources but as a community of spirits. In animistic traditions, every element of the natural world, whether it be a tree, a river, or a mountain, is seen as possessing a spiritual essence (Harvey, 2005). This perspective instills a sense of reverence and responsibility towards nature, as harming the environment is equated with disrespecting the spirits that inhabit it (Ingold, 2000). For instance, the belief in the sacredness of certain natural sites often leads to their protection and preservation, as they are considered the dwelling places of powerful spirits (Descola, 2013). This spiritual framework encourages sustainable interactions with the environment, emphasizing the need to maintain harmony and balance.

Moreover, the view of nature as a community of spirits fosters an ethic of care and stewardship. Animistic cultures typically engage in practices that ensure the well-being of both human and non-human members of this community. This holistic approach contrasts sharply with the exploitative tendencies seen in more anthropocentric worldviews (Bird-David, 1999). By recognizing the agency and intrinsic value of all natural entities, animism promotes a deep ecological consciousness that prioritizes the health of ecosystems over short-term human gains (Tsing, 2015). This perspective not only supports environmental protection but also aligns closely with contemporary principles of ecological sustainability and biodiversity conservation (Kohn, 2013).

4.2. Environmental Practices Rooted in Animism

Specific environmental practices and conservation efforts inspired by animistic beliefs illustrate the practical applications of this worldview. One notable example is the practice of sustainable hunting observed among the Inuit and other indigenous Arctic communities. These groups adhere to strict taboos and rituals that ensure respect for the spirits of the animals they hunt. Such practices include offering the first catch of the season back to the sea or performing ceremonies to honor the animal’s spirit, which in turn promotes sustainable hunting practices and prevents overexploitation (Nuttall, 1998).

Another significant practice rooted in animism is the preservation of sacred groves. In many African and Asian cultures, certain forests are considered sacred and are protected as the abodes of deities or ancestral spirits. These sacred groves serve as biodiversity hotspots and are often some of the last refuges for endangered species (Gadgil & Vartak, 1976). The protection of these areas is maintained through cultural taboos and community enforcement, demonstrating a successful model of community-based conservation (Hughes & Chandran, 1997). These practices highlight how animistic beliefs can lead to effective environmental stewardship and the preservation of natural habitats, aligning with modern conservation goals.

4.3. Modern Environmental Movements and Animism

Contemporary environmental movements increasingly draw inspiration from animistic principles, incorporating these ideas into their advocacy and practices. Movements such as Deep Ecology and Ecospirituality emphasize the intrinsic value of all living beings and the interconnectedness of life, concepts that resonate strongly with animistic worldviews (Devall & Sessions, 1985). These movements argue for a profound shift in human consciousness, advocating for a relationship with nature based on respect, reciprocity, and a recognition of the spiritual dimensions of the natural world (Taylor, 2010). By integrating animistic perspectives, modern environmentalists seek to foster a more ethical and sustainable approach to environmental protection.

Furthermore, the rise of indigenous-led environmental activism has brought animistic principles to the forefront of global conservation efforts. Indigenous groups often frame their environmental struggles in terms of protecting sacred lands and the spirits that reside within them (Laudine, 2009). This spiritual framing not only strengthens their claims but also resonates with broader audiences, garnering support for their causes. For instance, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline was articulated through an animistic lens, highlighting the sacredness of the land and water (Estes, 2019). These examples demonstrate how animistic beliefs can empower contemporary environmental movements, providing a rich ethical and spiritual foundation for advocating ecological sustainability and justice.

5. Impact of Colonialism and Modernization

5.1. Suppression of Animistic Traditions

5.1. Suppression of Animistic Traditions

Colonialism and modernization have profoundly impacted animistic traditions, often leading to their suppression and marginalization. European colonizers, driven by a mission to “civilize” indigenous populations, frequently dismissed animistic beliefs as primitive or superstitious, imposing their own religious and cultural frameworks (Comaroff & Comaroff, 1991). This imposition often involved violent suppression of indigenous practices, such as the destruction of sacred sites and the banning of rituals. For example, in Africa, colonial authorities outlawed many traditional ceremonies and replaced them with Christian practices, aiming to erase indigenous spiritual systems (Ranger, 1993). Such actions not only disrupted the spiritual lives of indigenous peoples but also eroded the social structures and ecological knowledge embedded in these traditions.

Modernization further exacerbated the marginalization of animistic traditions through the spread of Western education, urbanization, and economic development. These processes often promoted Western scientific rationalism and materialism, which devalued and displaced indigenous spiritual knowledge (Escobar, 1995). In Southeast Asia, for instance, the rapid expansion of commercial agriculture and logging has not only led to environmental degradation but also to the loss of sacred landscapes central to animistic practices (Tsing, 2005). The pressure to assimilate into modern, capitalist economies has often forced indigenous communities to abandon their traditional ways of life, including animistic practices, in favor of more “modern” livelihoods (Scott, 2009). This dual assault of colonialism and modernization has significantly undermined the continuity of animistic traditions across the globe.

5.2. Loss and Preservation of Knowledge

The external influences of colonialism and modernization have resulted in the significant loss of traditional knowledge and practices among indigenous communities. Many animistic traditions, which were transmitted orally through generations, faced erosion as younger generations were educated in Western ways and distanced from their cultural roots (Battiste & Henderson, 2000). The displacement of communities from their ancestral lands, often driven by colonial land policies or modern development projects, further severed the connection to sacred landscapes and the ecological knowledge embedded in them (Baviskar, 2005). This loss of knowledge is not just cultural but also ecological, impacting biodiversity conservation practices that were intertwined with these animistic traditions (Gadgil, Berkes, & Folke, 1993).

Despite these challenges, there are concerted efforts to preserve and revive animistic knowledge and practices. Indigenous communities and scholars are increasingly documenting traditional ecological knowledge and advocating for its inclusion in contemporary environmental management (Berkes, 2012). In Australia, for example, Aboriginal groups are working to revive traditional fire management practices, which are deeply rooted in animistic understandings of the landscape and have proven effective in reducing wildfire risks (Langton, 1998). Additionally, cultural revitalization movements are emerging within many indigenous communities, aiming to restore traditional practices, languages, and spiritual beliefs. These efforts often involve intergenerational knowledge transfer, community-led education programs, and collaborations with academic institutions to ensure that animistic traditions continue to thrive in the modern world (Smith, 1999).

5.3. Resistance and Resilience

Indigenous communities have shown remarkable resistance and resilience in maintaining their animistic beliefs and practices despite external pressures. In many cases, these communities have adapted their traditions to new circumstances, ensuring their survival and relevance in the face of colonization and modernization. For instance, the Maori of New Zealand have revitalized their traditional spiritual practices through the establishment of cultural schools and the integration of Maori knowledge into national education curricula (Walker, 2004). This resurgence is part of a broader movement to assert Maori identity and sovereignty, demonstrating the resilience of animistic traditions in the face of historical suppression (Durie, 1998).

Similarly, in North America, Native American tribes have fought to protect their sacred sites and cultural practices from encroachment by development and industrial projects. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline is a notable example, where the tribe framed their opposition in terms of protecting sacred water and land (Estes, 2019). This resistance not only highlighted the spiritual significance of the land but also galvanized international support, showcasing the enduring power of animistic beliefs in mobilizing environmental justice movements (Whyte, 2017). These stories of resistance and resilience underscore the ongoing vitality of animistic traditions and their critical role in contemporary struggles for cultural and environmental preservation.

6. Resurgence of Animism in Contemporary Spiritual Movements

6.1. Modern Spirituality and Animism

In recent years, there has been a notable resurgence of interest in animism among modern spiritual movements. This growing interest can be attributed to a desire for more holistic and interconnected worldviews, which contrast sharply with the often fragmented and materialistic perspectives of contemporary society (Harvey, 2013). Animism, with its emphasis on the interconnectedness of all life and the spiritual significance of nature, offers an appealing alternative for those disillusioned with mainstream religious and secular paradigms (Hornborg, 2006). Many individuals are drawn to animistic beliefs as a way to reconnect with nature, seeking a deeper sense of belonging and purpose in a world facing environmental crises (Taylor, 2010). This resurgence is also fueled by the broader cultural movement towards sustainability and ecological consciousness, wherein animistic perspectives are seen as vital to fostering a more sustainable relationship with the environment (Kohn, 2013).

Moreover, the digital age has facilitated the spread of animistic ideas through online communities, social media, and various forms of digital media, making these ancient beliefs more accessible to a global audience (Harvey, 2005). These platforms enable the sharing of knowledge and practices, allowing for a modern reinterpretation of animistic traditions that resonate with contemporary values and lifestyles (Ingold, 2000). Additionally, the increased visibility and advocacy of indigenous cultures and their spiritual practices have played a crucial role in the revival of animism, as many people look to these traditions for wisdom and guidance in navigating the complexities of modern life (Smith, 1999). This intersection of ancient wisdom and modern challenges highlights the enduring relevance of animistic beliefs in fostering a spiritually and ecologically harmonious world.

6.2. Integration with New Age Practices

Animistic concepts have increasingly found their way into New Age spirituality and other contemporary practices, creating a rich tapestry of spiritual exploration and expression. New Age spirituality, characterized by its eclectic and syncretic nature, readily incorporates elements from various traditions, including animism, to construct a personalized spiritual path (Hanegraaff, 1998). This integration often involves the adoption of practices such as shamanic journeying, spirit animal guidance, and rituals honoring the natural world, which are central to many animistic traditions (Eliade, 1964). These practices resonate with New Age seekers who value direct spiritual experiences and personal empowerment, finding in animism a profound connection to the living world around them (Beyer, 2009).

This blending of animistic and New Age elements is also evident in the holistic health and wellness industry, where concepts like energy healing, crystal therapy, and nature-based mindfulness practices are gaining popularity (Pike, 2004). These practices often draw on animistic beliefs about the spiritual essence of natural objects and the healing power of nature (Harvey, 2013). For example, the use of crystals in healing is rooted in the animistic idea that stones and minerals possess distinct spiritual energies that can influence human well-being (Kraft, 2017). Additionally, the resurgence of interest in plant medicine and psychedelic experiences, such as the use of ayahuasca in shamanic ceremonies, reflects a broader cultural trend towards embracing animistic practices for their transformative and healing potentials (Luna, 1986). This integration highlights the adaptability and enduring appeal of animistic concepts in contemporary spiritual landscapes.

6.3. The Future of Animism

The future of animism in the modern world appears promising, as it continues to influence and shape contemporary spiritual and environmental paradigms. The integration of animistic values into modern life could foster a more harmonious and respectful relationship with the natural world, addressing some of the pressing ecological challenges of our time (Descola, 2013). As more people recognize the ecological wisdom embedded in animistic traditions, there is potential for these beliefs to influence global environmental policies and practices, promoting sustainability and conservation in ways that are respectful of indigenous knowledge (Berkes, 2012).

Additionally, the resurgence of animism could contribute to a broader spiritual renaissance, providing an alternative to the often mechanistic and reductionist views prevalent in modern secular society (Harvey, 2005). As individuals continue to seek deeper connections and meaning, the holistic and inclusive nature of animistic beliefs can offer a pathway to spiritual fulfillment and a sense of belonging within the greater web of life (Taylor, 2010). The increasing recognition and respect for indigenous cultures and their spiritual practices can help preserve and revitalize animistic traditions, ensuring their transmission to future generations (Smith, 1999). This resurgence of animism, both as a spiritual and ecological paradigm, suggests that it will continue to play a vital role in shaping the future of human societies, fostering a more interconnected and sustainable world.

7. Conclusion

The resurgence of animism within contemporary spiritual movements underscores a significant shift in how individuals perceive and interact with the world around them. Modern spirituality’s growing interest in animism highlights a collective yearning for holistic and interconnected worldviews that contrast sharply with the fragmented, materialistic perspectives often found in today’s society. This renewed interest is driven by a desire to reconnect with nature and find deeper meaning and purpose in life, especially in the face of environmental crises. The integration of animistic concepts into New Age practices further exemplifies this trend, as people adopt shamanic rituals, spirit animal guidance, and nature-based mindfulness practices to enhance their spiritual experiences. The blending of these ancient beliefs with contemporary practices, such as holistic health and wellness, demonstrates the adaptability and enduring appeal of animistic traditions. The increasing visibility and advocacy of indigenous cultures also play a crucial role in this revival, as many look to these traditions for wisdom and guidance in navigating modern life’s complexities.

Looking to the future, animism holds significant potential for shaping both spiritual and environmental paradigms in contemporary society. As awareness of environmental issues grows, animism’s emphasis on the sacredness of nature and the interconnectedness of all life forms offers a compelling framework for ecological ethics and sustainable living. This perspective is increasingly recognized in environmental movements and policies, where indigenous knowledge and animistic principles contribute to biodiversity conservation and sustainable resource management. The spiritual landscape is also evolving, with animism providing a counterbalance to the mechanistic and reductionist views prevalent in modern secular society. The holistic and inclusive nature of animistic beliefs offers a pathway to spiritual fulfillment and a sense of belonging within the greater web of life. By respecting and revitalizing these traditions, we can ensure their transmission to future generations, fostering a more interconnected and sustainable world. Thus, the resurgence of animism is not just a return to ancient practices but a vital part of shaping a harmonious and balanced future.

8. References

Allen, C. J. (2002). The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga Whakaaro: Key Concepts in Maori Culture. Oxford University

Battiste, M., & Henderson, J. (Sa’ke’j) Y. (2000). Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge. Purich Publishing.

Baviskar, A. (2005). In the Belly of the River: Tribal Conflicts over Development in the Narmada Valley. Oxford University Press.

Berkes, F. (2012). Sacred Ecology. Routledge.

Beyer, S. V. (2009). Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon. University of New Mexico Press.

Bird-David, N. (1999). “Animism” Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40(S1), S67-S91.

Bocking, B. (1997). A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. Curzon Press.

Brown, J. E. (1953). The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux. University of Oklahoma Press.

Comaroff, J., & Comaroff, J. (1991). Of Revelation and Revolution, Volume 1: Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa. University of Chicago Press.

Descola, P. (2013). Beyond Nature and Culture. University of Chicago Press.

Devall, B., & Sessions, G. (1985). Deep Ecology: Living as if Nature Mattered. Gibbs Smith.

Durie, M. (1998). Te Mana, Te Kāwanatanga: The Politics of Māori Self-Determination. Oxford University Press.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Princeton University Press.

Escobar, A. (1995). Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton University Press.

Estes, N. (2019). Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. Verso Books.

Gadgil, M., Berkes, F., & Folke, C. (1993). Indigenous Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. Ambio, 22(2-3), 151-156.

Gadgil, M., & Vartak, V. D. (1976). The Sacred Groves of Western Ghats in India. Economic Botany, 30(2), 152-160.

Hallowell, A. I. (1960). Ojibwa Ontology, Behavior, and World View

Hanegraaff, W. J. (1998). New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. SUNY Press.

Harvey, G. (2005). Animism: Respecting the Living World. Columbia University Press.

Harvey, G. (2013). The Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Acumen Publishing.

Hornborg, A. (2006). Animism, Fetishism, and Objectivism as Strategies for Knowing (or Not Knowing) the World. Ethnos, 71(1), 21-32.

Hughes, J. D., & Chandran, M. D. S. (1997). Sacred Groves Around the Earth: An Overview. Conservation Biology, 11(6), 314-316.

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. Routledge.

Kohn, E. (2013). How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. University of California Press.

Kraft, S. E. (2017). The Religion of the Market and the Commodification of Religious Practices. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 32(1), 1-17.

Langton, M. (1998). Burning Questions: Emerging Environmental Issues for Indigenous Peoples in Northern Australia. Centre for Indigenous Natural and Cultural Resource Management, Northern Territory University.

Laudine, C. (2009). The Land is Our History: Indigeneity, Law, and the Settler State. Oxford University Press.

Luna, L. E. (1986). Vegetalismo: Shamanism Among the Mestizo Population of the Peruvian Amazon. Stockholm University Press.

Nuttall, M. (1998). Protecting the Arctic: Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Survival. Routledge.

Pike, S. (2004). New Age and Neopagan Religions in America. Columbia University Press.

Ranger, T. O. (1993). The Invention of Tradition Revisited: The Case of Colonial Africa. In The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, 211-262. Cambridge University Press.

Rivière, P. (1999). The Forgotten Frontier: A History of the Sixteenth-Century Ibero-African Frontier. Longman.

Scott, J. C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Zed Books.

Taylor, B. (2010). Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future. University of California Press.

Titiev, M. (1944). Old Oraibi: A Study of the Hopi Indians of Third Mesa. Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton University Press.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press.

Walker, R. (2004). Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End. Penguin Books.

Whyte, K. P. (2017). The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice, and U.S. Colonialism. Red Ink: An International Journal of Indigenous Literature, Arts, & Humanities, 19(1), 154-169.

ByKus

ByKus Historia

Historia Logos

Logos Humanitas

Humanitas Mythos

Mythos Theologia

Theologia Persona

Persona Quid

Quid Gestae

Gestae Politico

Politico Mundialis

Mundialis Oeconomia

Oeconomia Athletica

Athletica Technologia

Technologia Medicina

Medicina Scientia

Scientia Astronomia

Astronomia Academia

Academia Lingua

Lingua Bibliotecha

Bibliotecha Instutia Online

Instutia Online Naturales

Naturales Humaniores

Humaniores Aesthetica

Aesthetica Cinemania

Cinemania Pictura

Pictura Sculptura

Sculptura Architectura

Architectura Musica

Musica Artificia

Artificia Atari

Atari