1. Introduction

Cuneiform, the earliest known system of writing, marks a monumental leap in human communication and societal development. Originating in ancient Mesopotamia around 3200 BCE, this script was initially devised by the Sumerians and later adapted by several neighboring cultures, including the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians (Walker, 1987). Cuneiform inscriptions were etched on clay tablets using a reed stylus, a method that preserved a wide array of texts that have survived millennia (Nissen, 1988). The decipherment of cuneiform has been a pivotal scholarly achievement, opening a window into the social, political, and economic aspects of ancient Near Eastern civilizations (Robson, 2008). Understanding these texts has transformed our comprehension of ancient laws, treaties, and daily administrative practices, as well as literary and scientific accomplishments (Veldhuis, 2004). The continued study of cuneiform is crucial for comprehending the complexities of early human civilizations and their contributions to later societies (Foster, 1996). Through exploring this ancient script, scholars and enthusiasts alike delve into the thought processes and cultural values of some of humanity’s earliest empires.

2. Origins and Development of Cuneiform

2.1. The Earliest Writing System

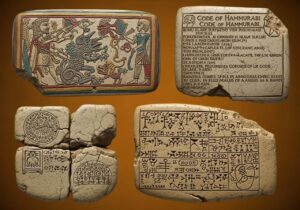

Cuneiform’s inception as one of the earliest writing systems is deeply intertwined with the urbanization and administrative needs of ancient Mesopotamia. Around 3200 BCE, as societies grew and complex administrative systems emerged, there was a pressing need to record transactions, inventories, and decrees, which ushered in the era of proto-writing (Schmandt-Besserat, 1992). The initial forms of cuneiform were pictographic, representing objects and concepts directly. These pictograms were impressed onto wet clay tablets with a stylus made from a reed, marking the beginning of recorded history (Nissen et al., 1993).

As the use of cuneiform evolved, the script underwent significant changes, transitioning from these pictographic representations to a more abstract, syllabic, and eventually phonetic system. This evolution reflects a shift from simple notational systems to a complex language able to convey abstract and philosophical ideas (Postgate, 1992). The phonetic nature of cuneiform allowed for the recording of multiple languages and dialects, highlighting its adaptability and sophistication as a writing system (Michalowski, 1993).

2.2. Spread and Adaptation

The spread of cuneiform across ancient civilizations is a testament to its functional and cultural adaptability. Originally developed by the Sumerians, the script was soon adopted and modified by surrounding cultures, including the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hittites (Foster, 1996). Each adopted version of cuneiform retained core elements but also reflected unique linguistic and stylistic traits specific to each culture (Veldhuis, 2004).

For instance, when the Akkadian Empire rose to prominence, they adapted the Sumerian script to their own Semitic language, creating a version of cuneiform that could express the sounds of Akkadian more effectively (Walker, 1987). Similarly, the Hittites, who encountered cuneiform during their conquests in Mesopotamia, incorporated it into their own language and administrative practices, demonstrating the script’s versatility across different linguistic groups (Bryce, 2005).

2.3. Materials and Writing Implements

The primary material for cuneiform writing was clay, chosen for its abundant availability and ease of molding and inscribing while wet. Once inscribed, the tablets were either sun-dried or baked to preserve the text, making cuneiform documents incredibly durable (Oates, 1986). This durability is a key reason why so many cuneiform tablets have survived to this day, providing a wealth of information about ancient Near Eastern civilizations.

The stylus, typically made from a reed, was the essential tool for writing cuneiform. Scribes would use the stylus to impress wedge-shaped marks into the clay, a technique that required significant skill and training. The art of writing cuneiform was thus highly specialized, often confined to a professional class of scribes who underwent extensive education in scribal schools (Robson, 2001). These scribes played a crucial role in the administration and culture of ancient societies, crafting documents ranging from bureaucratic records to literary and religious texts.

3. Decipherment and Scholarly Efforts

3.1. Early Attempts at Decipherment

The journey to decipher cuneiform began in the 18th century when European scholars first encountered cuneiform inscriptions during explorations in the Middle East. Initially, these ancient scripts were a complete mystery, with scholars unable to identify even the languages used in the texts (Friedrich, 1999). The early decipherment attempts were often misguided due to a lack of comparative material and an incomplete understanding of the historical context surrounding the artifacts (Daniels, 1996).

Challenges in these early stages were abundant. The script had changed over millennia, used by different cultures, and evolved into various dialects. This complexity made it extremely difficult for scholars to find a starting point. Moreover, the political instability in the regions where these tablets were found often hampered efforts to recover more texts that could provide much-needed context for the scripts (Kramer, 1986).

3.2. Breakthrough Discoveries

A significant breakthrough in the decipherment of cuneiform came with the work of Georg Friedrich Grotefend in the early 19th century. Grotefend made the first successful attempt to decipher ancient Persian cuneiform inscriptions, identifying several royal names which laid the groundwork for further decipherments (Cereti, 1997). Following Grotefend, Henry Rawlinson, a British army officer, expanded on these initial findings and managed to decipher the Behistun Inscription, which proved to be crucial in understanding the Old Persian language (Adkins, 2003).

The Rosetta Stone, although primarily associated with the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs, also played a symbolic role in the study of cuneiform by demonstrating that bilingual or trilingual texts could provide the keys to unlocking ancient languages (Robinson, 2009). Other significant finds, such as the multilingual inscriptions at Persepolis, helped scholars compare the cuneiform script with other known scripts, further facilitating the decipherment process (Simpson, 1997).

3.3. Modern Advancements

In recent decades, the study and decipherment of cuneiform texts have been revolutionized by digital technology and collaborative international projects. High-resolution imaging and 3D scanning have allowed scholars to read texts that are physically undecipherable to the naked eye, revealing new layers of information (Frahm, 2011). Furthermore, databases and collaborative online platforms have enabled a more systematic study of cuneiform, bringing together experts from around the world to share insights and data (Veldhuis, 2012).

Current research in the field of Assyriology and Sumerology continues to thrive with ongoing projects such as the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL) and the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). These efforts not only aid in the transcription and translation of texts but also in the broader analysis of social, economic, and cultural patterns in ancient Mesopotamian civilizations (Tinney, 1998; George, 2003).

4. Cuneiform Texts and Their Significance

4.1. Literary and Historical Records

Cuneiform writing has bequeathed to us a rich tapestry of literary and historical records that illuminate the lives and beliefs of ancient civilizations. Among these are epic poems such as the “Epic of Gilgamesh,” which not only offers insight into the mythological and cultural milieu of ancient Mesopotamia but also addresses universal themes of friendship, heroism, and the quest for immortality (George, 2003). Additionally, royal inscriptions and annals, such as those of the Assyrian kings, provide detailed accounts of military campaigns, religious practices, and administrative details, crucial for understanding the political and social structures of the time (Grayson, 1991).

The significance of these texts is profound. They allow modern scholars to reconstruct events that shaped the ancient Near East and provide a direct voice from civilizations long vanished. For instance, the Babylonian Chronicles provide a year-by-year account of Babylonian history, invaluable for corroborating dates and events mentioned in other contemporary sources, including the Bible (Wiseman, 1956). These texts not only enrich our understanding of ancient history but also enhance our appreciation for the literary expressions that predate and perhaps influence modern storytelling (Dalley, 1989).

4.2. Scientific and Scholarly Works

The scientific texts written in cuneiform reveal that the ancient Mesopotamians possessed sophisticated knowledge and understanding across various domains. Astronomical tablets, such as those from Babylon, exhibit detailed observations of celestial movements and have provided modern historians with data to calculate the accuracy of ancient astronomical knowledge (Rochberg, 2004). Similarly, mathematical texts demonstrate a complex understanding of geometry, algebra, and arithmetic, which facilitated the construction of architectural marvels and the development of trade and economics in these ancient societies (Friberg, 2007).

The contributions of these scholarly works to human knowledge are substantial. They reflect the early human endeavor to understand and manipulate the natural world through systematic observation and calculation. For example, the cuneiform tablets containing medical texts show not only the Mesopotamians’ approaches to diagnosis and treatment but also their spiritual beliefs interwoven with their medical practices (Böck, 2014). These texts underscore the interdisciplinary nature of ancient scholarship and its influence on subsequent intellectual pursuits in the Hellenistic and Islamic worlds, shaping early scientific thought (Høyrup, 1996).

4.3. Legal and Administrative Documents

Cuneiform was also used extensively for legal and administrative purposes, with thousands of clay tablets documenting the bureaucratic, legal, and commercial life of Mesopotamia. These include laws like the Code of Hammurabi, one of the earliest and most complete written legal codes, which has been fundamental in understanding justice and law in ancient times (Van De Mieroop, 2005). Additionally, contracts, receipts, and administrative records provide insight into the daily life, economic conditions, and governmental operations of these ancient civilizations (Veenhof, 2003).

These documents are crucial for understanding the social fabric and governance of ancient societies. They reveal the legal rights of citizens, the obligations of public officials, and the societal norms that govern behavior. The detailed records of commercial transactions and state administration illustrate the complexity of ancient economies and the sophistication of their governance systems. This information is invaluable for historians and archaeologists seeking to reconstruct the socio-economic landscape of the ancient Near East (Postgate, 1992).

5. Conclusion

The decipherment of cuneiform script was a monumental achievement that opened a window into the ancient world, revealing the complexities of societies that flourished thousands of years ago. This ancient script, once the administrative and literary backbone of several empires in the Near East, has provided historians and archaeologists with priceless insights into the socio-political structures, economic systems, religious beliefs, and daily lives of people in ancient Mesopotamia and surrounding regions. The recovery and translation of these texts have reshaped our understanding of history, proving that these civilizations were far more advanced in various aspects of culture and technology than previously believed. Through the study of cuneiform, we have discovered sophisticated legal systems, detailed astronomical records, and rich literary traditions that include some of the earliest known epic poems and philosophical treatises. These texts not only enrich our historical knowledge but also connect us with the human experiences and intellectual achievements of our ancestors.

The ongoing efforts to excavate, preserve, and interpret cuneiform texts continue to yield significant findings that promise to enhance our understanding of ancient history. Each new discovery has the potential to alter our perception of the past, providing fresh narratives and perspectives that challenge established historical frameworks. The digitalization of cuneiform tablets and the application of modern technologies such as AI and machine learning for decipherment and translation are accelerating these efforts, making it easier for scholars worldwide to access and study these ancient documents. Furthermore, collaborative international research projects and increased funding for archaeology in the Middle East are crucial for uncovering more texts and artifacts. As we continue to unravel the secrets held within these ancient clay tablets, we remain hopeful that each piece of cuneiform text brings us closer to a more comprehensive understanding of human history.

6. References

Adkins, L. (2003). Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Böck, B. (2014). The Healing Goddess Gula: Towards an Understanding of Ancient Babylonian Medicine. Brill.

Bryce, T. (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford University Press.

Cereti, C. G. (1997). The Iranian languages. Routledge.

Dalley, S. (1989). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press.

Daniels, P. T. (1996). The Study of Writing Systems. In Daniels, P. T., & Bright, W. (Eds.), The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press.

Frahm, E. (2011). History and Monumental Inscriptions. Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

Foster, B. R. (1996). Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature. Bethesda: CDL Press.

Friedrich, J. (1999). Extinct Languages. New York: Philosophical Library.

Friberg, J. (2007). A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts: Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts I. Springer.

George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press.

Grayson, A. K. (1991). Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC I (1114–859 BC). University of Toronto Press.

Høyrup, J. (1996). In Measure, Number, and Weight: Studies in Mathematics and Culture. SUNY Press.

Kramer, S. N. (1986). History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Michalowski, P. (1993). Sumerian Language. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Nissen, H. J., Damerow, P., & Englund, R. K. (1993). Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East. University of Chicago Press.

Nissen, H. J. (1988). The Early History of the Ancient Near East, 9000-2000 B.C. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Oates, J. (1986). Babylon. Thames and Hudson.

Postgate, J. N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge.

Robinson, A. (2009). Writing and Script: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Robson, E. (2001). Mesopotamian Mathematics, 2100-1600 BC: Technical Constants in Bureaucracy and Education. Oxford Editions of Cuneiform Texts.

Robson, E. (2008). Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rochberg, F. (2004). The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge University Press.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1992). Before Writing: From Counting to Cuneiform. University of Texas Press.

Simpson, E. (1997). The Persepolis Fortification Tablets. American Journal of Archaeology.

Tinney, S. (1998). Texts, Tablets and Teaching: Scribal Education in Nippur and Ur. Expedition Magazine.

Veenhof, K. R. (2003). Cuneiform Archives and Libraries. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Veldhuis, N. (2012). Education and Training of Scribes in Sumer. Journal of Cuneiform Studies.

Veldhuis, N. (2004). Religion, Literature, and Scholarship: The Sumerian Composition Nanše and the Birds. Cuneiform Monographs, 22. Groningen: Styx.

Van De Mieroop, M. (2005). King Hammurabi of Babylon: A Biography. Blackwell Publishing.

Walker, C. B. F. (1987). Reading the Past: Cuneiform. London: British Museum Press.

ByKus

ByKus Historia

Historia Logos

Logos Humanitas

Humanitas Aesthetica

Aesthetica Cinemania

Cinemania Lingua

Lingua Mythos

Mythos Theologia

Theologia Bibliotecha

Bibliotecha Persona

Persona Quid

Quid News

News Politico

Politico Mundialis

Mundialis Oeconomia

Oeconomia Athletica

Athletica Technologia

Technologia Medicina

Medicina Scientia

Scientia Astronomia

Astronomia